Heads

In Heads, Doug Heslop presents a series of portraits of men who abused children, or who enabled that abuse. The cover-up of their crimes came to light in the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, which concluded in 2017. The 26 portraits include priests and religious brothers, a lay church person and a youth worker, and painting them has not been an act of tribute or honour but an expression of disgust. Read More

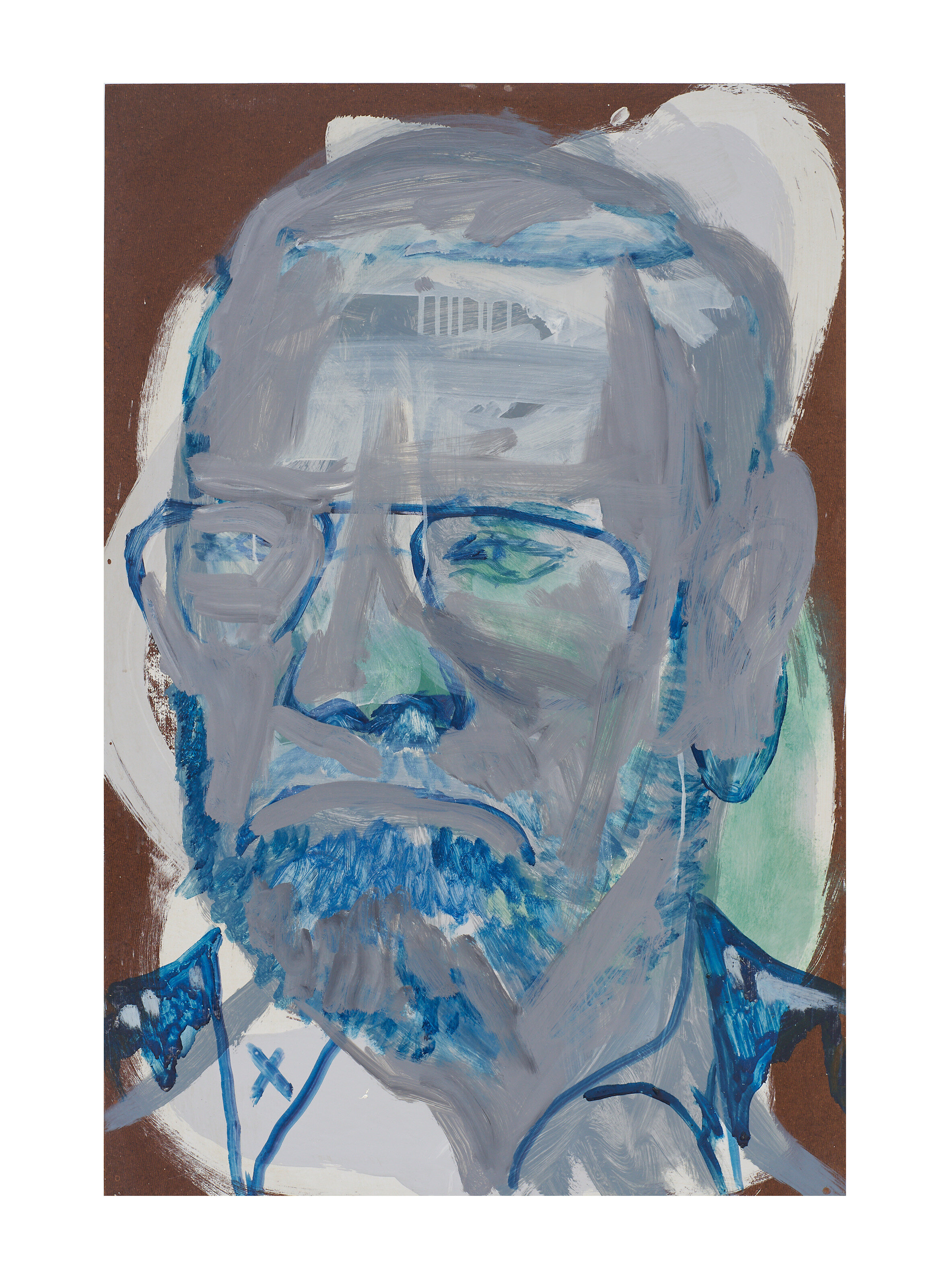

no.18

no.23

no.20

no.16

no.5

no.17

no.12

no.21

no.8

no.24

no.15

no.14

no.19

no.7

no.10

no.13

no.9

no.22

no.11

no.6

no.4

no.1

no.2

no.3

Heads

In Heads, Doug Heslop presents a series of portraits of men who abused children, or who enabled that abuse. The cover-up of their crimes came to light in the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, which concluded in 2017. The 26 portraits include priests and religious brothers, a lay church person and a youth worker, and painting them has not been an act of tribute or honour but an expression of disgust.

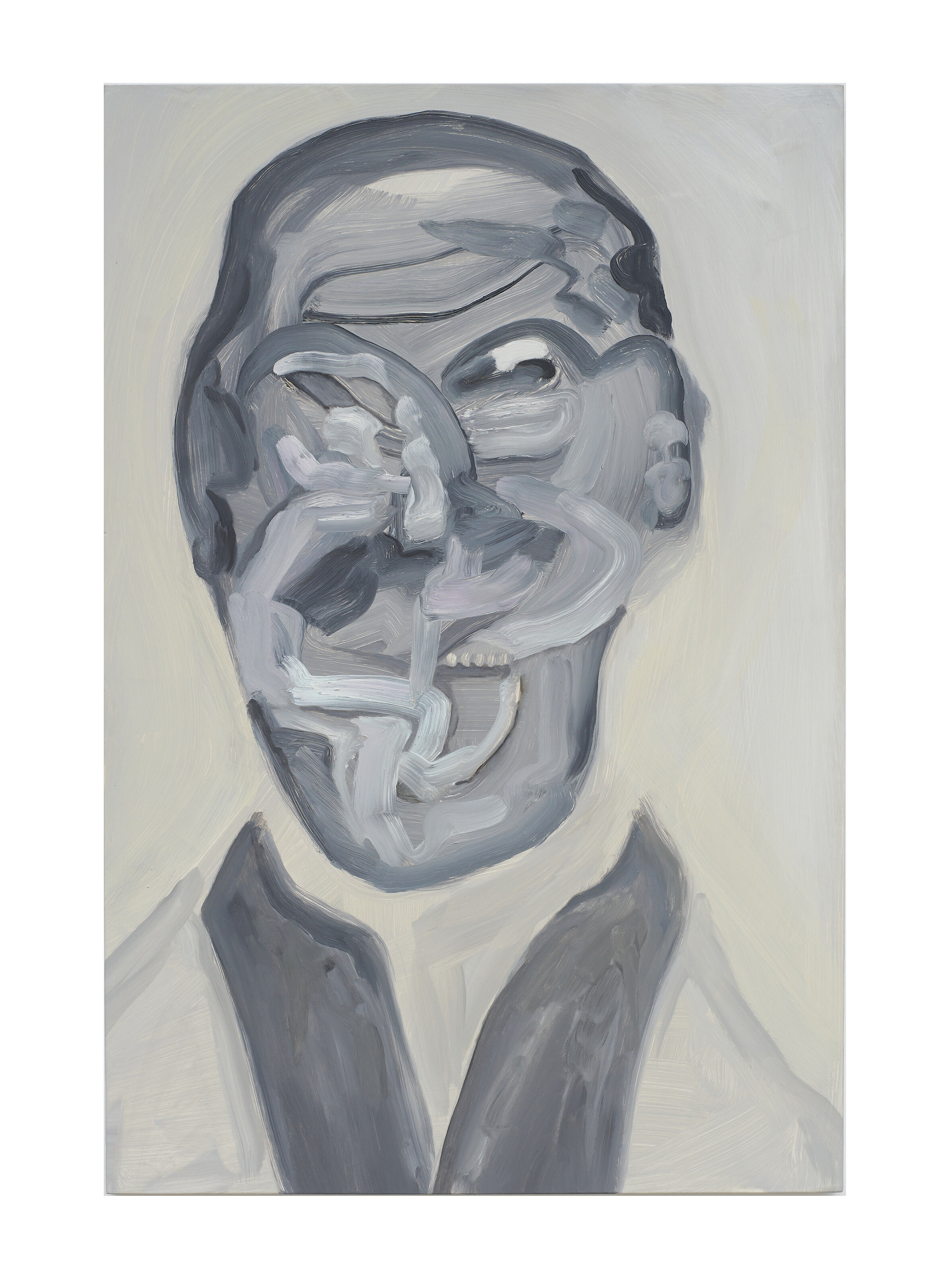

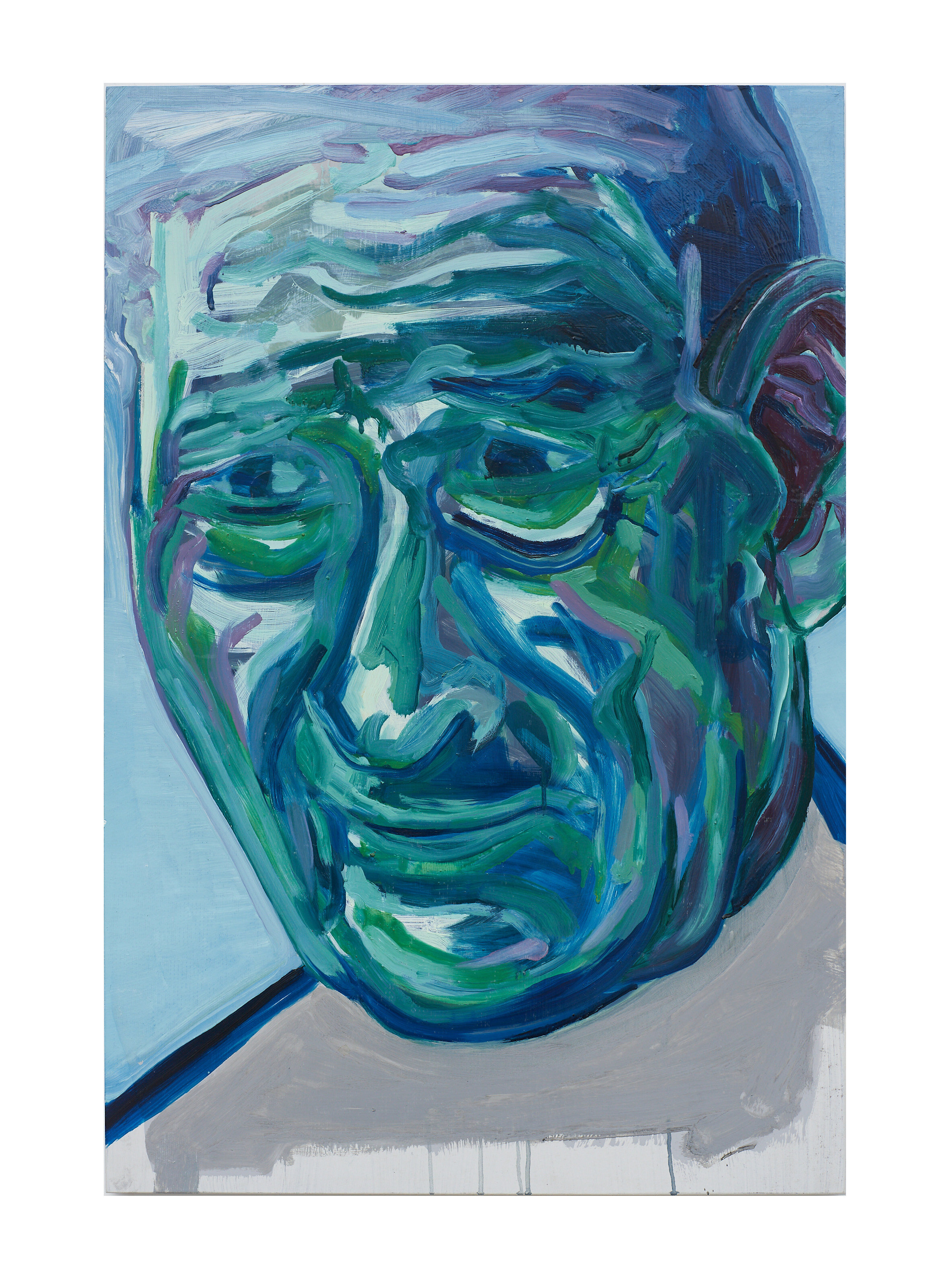

Heslop’s handling of paint is visceral. In Head 11, 2018, lines of fleshy, wormy pink crawl across the face. Another, Head 19, 2018, is a pallid, bloodless blue while Head 4, 2018, is a toxic, unnatural purple. The photographs Heslop used for these portraits were taken from local newspaper coverage. Many of the men are smiling. One even looks heavenward. Others just appear startled, wide-eyed, belligerent, or simply gormless. Repentance is hard to find.

In some, Heslop has painted the facial features as though sliding in a foul, viscous fluid. Head 17, 2018, is almost entirely disfigured by brushstrokes. This physical distortion is a way of exposing spiritual and moral corruption, but it also asks about complicity. Since the Commission, the original photographs have become familiar to many and some degree of comparison is inevitable. How much was there to be seen? And why were those who did see it ignored?

The title of the series, Heads, alludes not just to traditions of portraiture but also the idea of hierarchies. The works focus on the head and shoulders. Small details like collars and crosses indicate position and status, however the bodies of the men are shadowy and amorphous. The backgrounds are tonal and empty but in Head 9, 2018, there is a small figure in a short-sleeve shirt and school tie. His presence is a heart-breaking reminder of the worlds these men moved through, and the access they had.

The tension here is about the banality of these single, weak men and the way their bodies remain largely out of sight. In this, Heslop has coopted the language of portraiture and shaped it into social critique, and attention turns to the hidden power structures propping the men up.

Heslop’s past bodies of work have engaged with forms of protest, and have questioned value systems both within the art world and wider society. Beyond the specific, horrifying cases behind these portraits, the Heads series is also a much broader provocation of our trust in canons, and the figures and tokens of authority.

When Heads was selected for the Blake Prize exhibition in 2018, twelve of the portraits were hung together in a row. Side-by-side like this, they spoke about strength in numbers, but the presentation also suggested the kinds of places where portraits are hung, calling to mind the many other corridors of power that run through our world. The men in Heslop’s Heads are just the local faces of a global problem, and their portraits are reminders that abuse of power has a long history.

Jane O’Sullivan, 2020